It’s no secret that I am concerned with management of the difficult airway, especially as pertains to the rural/remote/austere context. This may be either as a rural GP providing anaesthesia in the Operating Theatre, in the Emergency Department or at the roadside. Whilst many of us learn and regularly upskill in anaesthesia via the comfortable environment of the OT (usually under the tutelage of a FANZCA), the reality is that rural practice is limited by lac of immediate backup and often a paucity of equipment.

Airway difficulty may be encountered unexpectedly in the OT, or be anticipated in the dynamic airway of a critically ill patient in the ED or prehospital environment

Back in 2012 I published on the availability of equipment to manage the difficult airway in rural Australia, driven by the publication of ANZCA PS56 “Guidelines on Equipment to Manage the Difficult Airway”. As a result, recommendations could be made regarding airway equipment in an austere environment, especially on a budget – this might include standard direct laryngoscopy, videolaryngoscopy, both standard LMA and an intubating LMA as well as equipment to manage the emergency surgical airway. Similar setups are found in some prehospital services, with the FastTrach iLMA being the standard ‘go to’ device for rescue intubation attempts.

So I was interested to see the 2015 update on management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults from the UK Difficult Airway Society (shout out to them by the way – interested airway enthusiasts can join DAS for a nominal fee and have their say in future guideline development).

So – what’s new in DAS 2015?

The 2015 Guideline can be accessed here. These guidelines are driven by published evidence where available; where evidence is lacking, is directed by expert opinion via DAS. I think the paper is worth reading by ANY rural clinician, as well as those involved in airway management whether in prehospital, emergency department or operating theatre. Many of the topics discussed in FOAMed circles over the past few years are distilled into the DAS guidelines, finally.

Key features include :

- planning for failed intubation in both routine intubation and RSI

- extra emphasis on airway assessment including assessment of emergency surgical airway (ESA) or front-of-neck access (FONA)

- preparation, positioning, pre-oxygenation, maintenance of oxygenation via apnoeic diffusion oxygenation/NODESAT and minimising repeated attempts causing trauma

- importance of skills in both direct laryngoscopy and video-laryngoscopy for all anaesthetists

- use of second-generation supraglottic airway devices (SAD) to maintain oxygenation & ventilation

- importance of maintaining adequate muscle relaxation throughout difficult airway management, particularly to facilitate not only intubation attempts, but placement of SAD, face-mask ventilation and ESA/FONA.

- emphasis on scalpel cricothyroidotomy as the preferred ESA/FONA technique over needle techniques.

It’s particularly gratifying to see mention of cognitive aids for crisis management such as The Vortex, the technique of apnoeic diffusion oxygenation (NODESAT), use of rocuronium to give rapid onset of intubation conditions and to maintain adequate relaxation during subsequent airway management, as well as use of the laryngeal handshake’ – all topics familiar to the FOAMed community.

“DAS make it explicit that adoption of guidelines and professional acceptance alone are insufficient – such techniques need to be practiced and understood by all members of the anaesthetic team”

On top of this, there is emphasis on the value of human factors, with this contributing to at least 40% of adverse outcomes identified in NAP4. The new guidelines mention the impact of cognitive overload in a crisis, the need for structured communication tools such as PACE, the value of setting limits on intubation/SAD attempts, use of cognitive waypoints (“stop and think”), having a shared mental model and so on. Again this is nothing new, but it is worth pause and consideration of how often we actually train together – many of the airway courses are aimed at the airway operator (typically a doctor) and it is actually quite rare for teams to train together for crisis, unless part of a high-functioning unit such as a retrieval service or forward-thinking ED or ICU.

“I would be interested to hear from rural doctors – how many of you have the chance to train together fro crisis management using ALL team members via in situ sim?”

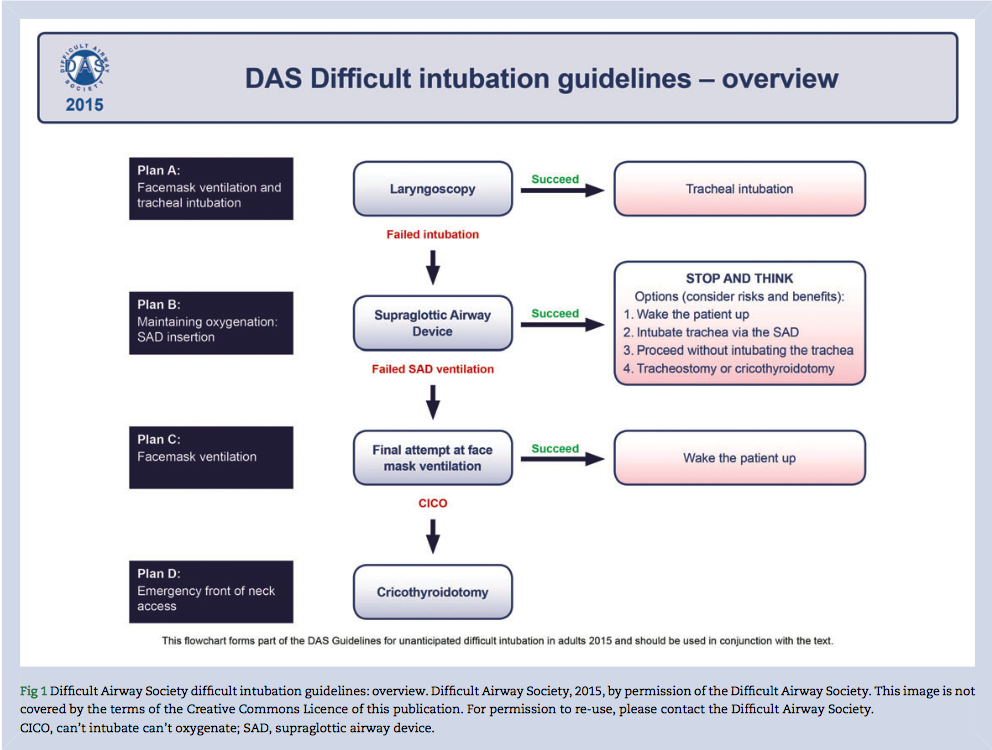

DAS Airway Plans A-B-C-D

Full discussion is best left to the actual 2015 guideline published 10-11-15 in BJA.

In brief the guidelines include:

PLAN A : Facemask Ventilation & Laryngoscopy

- Importance of head-up positioning and ramping are highlighted

- Preoxygenation for all patients; apnoeic diffusion oxygenation for high-risk patients

- Role for VL in addition to DL recognised, with statement that “all anaesthetists should be skilled in use of a videolaryngoscope”

- Cricoid pressure is stated as ‘a standard component of RSI in the UK’ and should be applied correctly (*)

- Maximum of three attempts, changing something between attempts (a fourth attempt by more experienced colleague is included as permissable’)

I won’t bore you all with the nuances of different VL devices, suffice it to say that DAS suggests their use be familiar to anaesthesia providers. In rural, we are often limited by available funds, making a compromise in cost and function. Many devices give excellent views of the glottic opening, which does not always translate into effective ETT delivery unless trained and practiced repeatedly.

“I think DAS missed a trick here – they mention cricoid pressure rather than taking the opportunity to describe it correctly as cricoid force”

Application of cricoid pressure is stated as ‘a standard component of RSI in the UK‘. The 2015 DAS guidelines acknowledge that cricoid needs to be applied properly to be effective and that is often inexpertly applied, thus making mask ventilation, direct laryngoscopy and SAD insertion more difficult. There is no mention of accepted modifications to RSI, including omission of cricoid, as practiced elsewhere in the world and accepted by certain airway providers as acceptable practice in airway management of the critically ill.

If fails, pre-agreed plan to move swiftly to:

PLAN B : Maintaining Oxygenation : Supraglottic Airway Device (SAD) Insertion

- Limiting insertion to three attempts, changing size/device

- Cricoid pressure should be removed during SAD placement

- Maintenance of oxygenation & ventilation

- Successful placement of a SAD creates a cognitive waypoint to “stop and think”

- All anaesthetists should be trained to use and have immediate access to second generation SADs

Subsequent options at the ‘stop and think’ stage may include :

- awakening the patient if possible

- make a further attempt at intubation via LMA s a conduit

- continue anaesthesia on SAD without placement of an endotracheal tube

- proceed directly to surgical airway

I think this is terribly exciting. First up, the DAS Guidelines make it explicit that we should be using second-generation supraglottic devices. I have reviewed some of these previously eg: Supreme & iGel in A Love Supreme and AirQ in Desert Island Airways.

The ideal device is characterised by reliable first-time placement, high seal pressure, integral bite block, separation of respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts and compatibility with fibreoptic devices. The latter is important when considering a ‘staged airway approach eg: placement of SAD in the field by trained EMS providers, allowing rapid intubation in the ED via FO using same SAD as a conduit.

“One could also consider the need for an integral bite block and lack of need for an inflatable cuff to be recommendations for a rescue SAD device”

The DAS algorithms previously advocated use of an intubating LMA to facilitate blind intubation as a rescue technique. Many theatres, emergency department sand even retrieval services have relied upon the FastTrach device. Whilst it has reportedly better blind intubation success than alternatives (eg: the Cook Gas Air-Q II device), I find the FastTrach to be bulky, expensive, fiddly to use unless specifically-trained. It also lacks a gastric drainage port – and whilst the device can be removed to leave an ETT in situ, this is a high-risk procedure which can result in inadvertent loss of the airway (for example, see the Gordon Ewing case).

In the past I have been a fan of the Air-Q device, mainly because it obviates the need for cuff inflation, has integral gastric drainage and is a great conduit for fibreoptic intubation, either by stylet or flexible scope. DAS acknowledge the many types of SADs on the market and make specific reference to the iGel, Proseal and Supreme LMAs as being supported in practice by large-scale longitudinal studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses.

“Is the FastTrach iLMA redundant under DAS 2015?”

One can argue the toss between iGel, Supreme and AirQ devices, but one thing seems clear from the 2015 DAS Guidelines – there is NO ROLE for blind intubation through an iLMA. Instead PLAN B necessitates use of a second generation SAD and pause to consider options as above (ie: awaken, place ETT, continue on SAD or perform ESA).

Most places where I have worked have kept the FastTrach as the accepted go to device, including in theatre, ED and in retrieval. I was always puzzled by the inclusion of a single size 4 FastTrach in the intubation pack of South Australia’s retrieval service – logic would dictate that a variety of sizes be carried, rather than rely on a single device. The lack of gastric drainage also irked me!

“Is there an excuse NOT to intubate using fibreoptic device via SAD as a conduit?”

But now the way forward is clear and appears supported by DAS 2015 – use a SAD for Plan B, and one which allows fibreoptic placement of an ETT over blind techniques which are “not recommended”. Logically this could be achieved via carrying a variety of second generation SADs as both rescue devices and as conduits for fibreoptic intubation – to my mind this could be via either the iGel, the Supreme or the AirQ…but of course now requires consideration of training and skills maintenance with a fibreoptic device. Whilst their availability is taken as a given in DAS, the reality is that very few rural doctors, EDs or even some prehospital providers will have access to what was traditionally expensive equipment. Of course there are low-cost solutions, such as the use of the Levitan intubating stylet or the AmbuAscope.

I think that these devices will see renewed interest and form part of a robust airway plan for use in rural and austere environments. Whilst AFOI techniques are hard to learn and maintain for occasional intubators, the placement of an ETT via SAD as conduit using eg: the Ambu Ascope is releatively straightforward and affordable even for cash-strapped rural hospitals.

For me the equation seems simple : second generation SAD + fibreoptic = robust safety

Here’s a video of my mate Geoff Healy at SydneyHEMS demonstrating the AmbuAscope for both awake fibreoptic intubation and via the iGel SAD as a robust technique in a mature and innovative prehospital service. These scopes are affordable and fairly straightforward to use when combined with the SAD as conduit technique. I think every rural hospital and ED should consider it to allow staged airway management in case of difficulty.

Thus I think it may be time to retire the FastTrach for blind intubation and switch to use of a SAD-fibreoptic combo. But promise me one thing – don’t throw out the Parker tip ETTs that come packed with the FastTrach – they are great for avoiding hangup on the right arytenoid!

PLAN C : Facemask ventilation (FMV)

If effective ventilation has not been established after three SAD insertion attempts, then Plan C should be enacted. By this stage Plans A & B have failed and the only remaining options are to awaken the patient with full reversal of neuromuscular blockade or to continue and perform an emergency surgical airway with ongoing paralysis.

Plan D : Emergency front-of-neck access (FONA)

In the past, various techniques for ‘needle’ vs ‘knife’ have been advocated. Most of us in Australia are familiar with the excellent work by Andy Heard and colleagues in WA, describing needle, knife and open techniques for cricothyroidotomy (see links at youtube channel here). Even in the post NAP4 era, it was not uncommon debate to hear experienced anaesthetists express a preference for needle cricothyroidotomy and a relaiance on the surgeon to perform a surgical airway with scalpel.

DAS 2015 make it clear that the scalpel technique is an expected skill of all anaesthetists, which must be learned and have regular training to avoid skill fade.

The laryngeal handshake is a technique I have been teaching on various airway courses & workshops, as well as on the ETMcourse, after being shown by Levitan on a cadaver course. It is simple to teach and reliable. Thus it is pleasing to see DAS 2015 make explicit this technique of identification of the cricothyroid membrane and subsequent entry.

DAS 2015 offer two options for FONA :

- identifiable anatomy – stab, twist, bougie, tube

- if unsuccessful or no identifiable anatomy – scalpel, finger, bougie, tube

To be fair, DAS 2015 does mention cannula techniques as options, but maintains that surgical cricothyroidotomy s both faster and more reliable – and again, emphasises that the scalpel technique is an expected skill of all anaesthetists, which must be learned and have regular training to avoid skill fade.

As an added extra, mention is made of the use of ultrasound as part of airway evaluation, with recommendation that training in it’s use is recommended for anaesthetists. I have certainly found it useful for identification of the trachea and cricothyroid membrane in difficult anatomy where time permits.

Summary

So, a quick rattle through the DAS 2015 guidelines for management on unanticipated difficult intubation (for both routine and rapid sequence intubation) in adults.

What does this mean for rural clinicians or those practicing in an austere environment? Perhaps no change from what many of us have been advocating for several years, namely

- be prepared for unexpected difficult airway management

- understand the importantce of human factors in crisis management and train accordingly

- use an agreed plan, articulated to team members regularly practiced with in situ sim

- be competent in both direct and videolaryngoscopy techniques

- minimise repeated attempts at intubation and SAD insertion; make FIRST attempt the BEST attempt using appropriate positioning (head up, ramping) and use apnoeic diffusion oxygenation in high-risk patients

- use a second generation supraglottic airway device

- maintenance of oxygenation and ventilation via SAD is a cognitive way point for the team to ‘stop and think’ before proceeding further

- blind intubation through an iLMA is no longer recommended; rather, place a SAD with integral gastric drainage and use as a conduit to intubate using a fibreoptic device

- maintenance of paralysis is essential to optimise intubation, SAD insertion, face-mask ventilation and ESA/FONA

- use of a scalpel to perform surgical cricothyroidotomy is an essential skill for anaesthetists and should be practiced regularly

A lot of this is covered in the ‘Airways on a Budget’ talk for rural doctors from a few years back

https://vimeo.com/51654548

There are plenty of other pearls in the 2015 Guidelines – have a browse and think how you will implement in your practice. We’ll be discussing some of this in the forthcoming Critically Ill Airway (CIA) course hosted by Chris Nickson at The Alfred in December. I will be one of the Faculty for what promises to be an interesting mix of task-trainign and hands on in situ simulation.

Game on…

References

Chrimes N & Fritz P The Vortex Approach Access here

Frerk et al (2015) Difficult Airway Society 2015 guidelines for management of unanticipated difficult intubation in adults British Journal of Anaesthesia doi 10.1093/bja/aev371

Leeuwenburg T (2015) Airway management of the critically ill patient: accepted modifications ot traditional rapid sequence induction & intubation Critical Care Horizons 1 Access here

Leeuwenburg T (2012) Access to difficult airway equipment & training for rural GP-anaesthetists in Australia Rural & Remote Health Access here

Sydney HEMS Fibreoptic Intubation using iGel and AmbuAscope – trainign video Access here

Weingart S. & Levitan R. (2011) Preoxygenation and prevention of desaturation during emergency airway management Annals of Emergency Medicine Access here

Blog Posts

KIDOCs Airway Classics – A Love Supreme

KIDOCS Desert Island Airways

Hello Tim

I admire your passion to improve acute care in remote centres.

The situations you describe are rare (even for high volume centre) and therefore the only way you can practice them is in the setting of simulation. I have never had to perform an emergency surgical airway (except one observed in theatre) in 20 years of EM city practise.

But just as the technical skills of airway management require repetition and refreshment, so do Crisis Management skills.

My colleague tells me there is some evidence that if a major hospital isn’t practising its disaster management protocol annually, it is unlikely they will perform optimally.

Therefore, what do you think is the current capacity in our system for all regional docs to either refine their skills or perform difficult airway scenarios under the guidance of experienced operators and supervisors.

And within this context should there be modified algorithms applicable to occasional or inexperienced operators rather than the assumptions made by a specialist society?

Regards,

Derek

Hi Derek

Au contraire – in terms of appropriateness of the DAS2015 guidelines, I would argue that same standard applies whether practicing anaesthesia in rural OT, in the ED, at the roadside or in a tertiary OT (although I think that one does need to accept modifications to traditional RSI as practiced in various areas of world and in certain circumstances, such as the omission of cricoid force in the prehospital environment or where skilled assistance is not guaranteed)

Similarly one COULD make an argument for omission of Plan C is circumstances where awakening is not an option – again relevant to prehospital or emergency airway management

In terms of training for rural doctors specifically, I do not think that it is necessary to rely purely on tutelage by the FANZCAs – whilst there is much to learn, the environment in which we operate is somewhat different and not always appreciated (the hoary old chestnut is the example of the former with blunt laryngeal trauma following a quad bike vs fencing wire incident – the FANZCA answer invariably involves a gas induction in theatre or use of AFOI…the pragmatic rural doctor without access to this just has to adopt another approach such as VL under ketamine/topicalisation or just meticulous attention to first pass success using DL and bougie – gently!)

Better to have such training BY rural clinicians FOR rural clinicians, delivered in situ using the kit available in a rural hospital

THIS is an area for improvement – currently in SA there is no audit of airway management in rural, let alone a cohesive approach to equipment and raining. The current modus operandi is for various hospitals to determine own equipment needs (guided, one hopes, by ANZCA PS56) and then individual clinicians to be familiar with guidelines and airway plans.

A better solution would be to have standardised airway equipment (such as the SCRAM bag or DAE trolley) containing

– DL and VL (C-Mac ideally, but failing tan an affordable cousin preferably with similar blade geometry as DL

– second generation supraglottic devices, coupled with affordable fibreoptic such as AmbuAscope to allow intubation via SAD conduit over the previously practiced blind iLMA positioning. iGel, Supreme or AirQ would be popular – and in SA, if SAAS go with iGel then suggest EDs and OTs do the same for skills maintenance

– BMV with PEEP

– ESA for FONA using scalpel-bougie/finger-size 6.0 ETT

The above is affordable for $3-5K (blows out to $20K if opt for the C-Mac, although again one wonders if economies of scale if purchase in bulk across units in SA Health)

In terms of rarity of ESA, I hear you and agree that regular training in crisis management is essential.. Again I would argue that this is best practiced in situ by rural clinicians for rural clinicians, utilising all members of the team – not by ‘doctor only’ courses under supervision of specialists

Derek, you mention the rarity of emergency surgical airways. My first was as an emergency trainee on anaesthetic rotation – and happened on the ward. Very unprepared, as was the team. Three more since then, which either means am crap at intubation OR have had an interesting case mix.

They are rare, but can sneak up.

More relevant, especially to YOUR situation in the ED, is the DAS2015 emphasis on maximising first pass success, minimising repeat attempts and moving to Plan B – ditch the old classic LMAs and mandate a second generation SAD. The inclusion of a ‘stop and think’ waypoint here is gold.

Similarly the move away from BLIND intubation through an iLMA such as the FastTrach is sensible – there are affordable devices out there such as AmbuAscope to allow fibreoptic intubation through a SAD conduit.

Again, a skill easily taught and trained in rural or austere context, as per Geoff Healy video from SydneyHEMS…

So easy even an EM doc could do it.

It is interesting how we can define expert here.

The reality is that there is no such thing as an expert in difficult airways who regularly practises in a remote location with an inexperienced team.

There may be anaesthetists who deal with this regularly in an elective setting or experiencers retrievalists who manage it remotely with a high-functioning team. There may even be those who have greater experience (such as yourself) but even that may be not be translatable to other clinicians in similar circumstances

The more important question is who should be the ones offering advice to those that lack expertise.

Any novel proposed solution will likely to be without higher levels of evidence and be based on the collaborative efforts of various stakeholders and ‘experts’ that are able to recognise the clinical and resources limitations that will be encountered.

The next challenge is being to able provide standardised and regular training to all practitioners who have the potential of encountering these scenarios.

Thanks Tim for the post and Derek for his comments

I think we get carried away by trying to figure out what the best airway equipment is. Derek is correct in that it is the training that is the key here. The equipment should not dictate the training, it should be around the other way.

The notion that we find the best airway kit and give it to all the rural doctors is misleading in my opinion.

yes there are standards advised for such things by colleges but as Derek points out, what an expert says for one situation may mean nothing for another situation. It is truly contextual.

I have managed and seen difficult airway cases in remote locations with flash teams, with basic airway gear and it is true that the best difficult airway equipment is the one you carry between your ears.

we dont want silly situations like having iGel and Ambu Ascope flexible scopes sitting in all rural EDs yet have no one there who is confident and skilled in using them. I can talk a nurse over the phone into inserting an iGel, no problem. I cannot talk a rural doctor over the phone who has only intubated 1-2 in 12 months to drive an Ambu Ascope. It would be far safer to talk them into inserting an iGel and doing a cricothyrotomy.

As for ditching the Fastrach , Tim? Sure if you want to, but I see no logic in doing that for something that has been proven to work many times in many studies. Its like arguing lets stop doing DL cause VL is so much better.

Guys, I think the issue is becoming confused.

First, you will get no argument from me re: the need for training over equipment, everytime. But such training needs to be relevant to the location in which practice

Second, the FastTrach. Good device for blind intubation. But let’s be clear – it’s not me saying this – it’s the DAS 2015 Guidelines saying that blind intubation via iLMA is not recommended

Third, let’s also be specific about who we are talking about. Minh I think it’s a straw man to confuse the isolated rural GP and the rural GP-anaesthetist. I am not talking about encouraging the use of fancy kit (and it is fancy) for use by the inexperienced.

Three scenarios

(a) the occasional airway operator in Dingo Creek. Keep it simple – avoid intubation if at all possible. Use second gen LMA. Dont go faffing around with fibreoptic (even as conduot) unless trained

(b) the more experienced rural EM doctor – whether in metro or rural – have skills across DL-VL-SAD and of course surgical airway. One point I think Derk is missing is the potential for a staged airway approach. Imagine the SA Ambulance ambos arrive in the ED with a post-OOHCA patient. hey’ve placed an iGel already and are ventilating. You now have choice – leave it in, take it out and intubate formally (with concomitant delay) or – and I like this option if have the kit – drop in an ETT via the iGel as conduit using a device such as Ascope

(c ) Use by the rural GP-anaesthetist. He/she is already providing anaesthetic care to both elective and emergency patients, although in a potentially austere environment (no immediate back up). They probably have more airway training and certainly more skills maintenance than most FACEMs, at least in theatre. They are also in the potentially difficult space of being ‘the expert’ when called in to an airway crisis in the rural ED. There is a good argument therefore for both having the training and ongoing skills for a robust airway strategy, both for unexpected airway difficulty in OT or in ED. Skills in DL and VL for sure. Use of a second generation LMA over the classic – definitely. The Plan B option in DAS is nice now as affords opportunity to ‘stop and think’ – awaken if feasible in OT, continue on LMA…place an ETT (or rarely proceed to rescue FMV and CICO)

If the decision is made to place an ETT, we should be able to do so in the best way. remember I am talking about rural GP-anaesthetists here, not about the isolated rural G with minimal airway skills. FastTrach as allowed blind intubation int he past and indeed is relatively easily taught, has a good track record (I know RFDS Qld have used in anger!). However the placement of ETT is blind; moreover the FastTrach iLMA doesnt have a gastric drainage port and is a nightmare to remove.

hence the interest in using SAD as a conduit – maintain ventilation, drop in an ETT via Ascope. A skill that can be easily acquired through task training on mannikins and practice in theatre in elective setting. But not one to be ‘talking through on the end of the phone’ as per Minh’s straw man

For sure, hope never to use it. But for those tasked with providing anaesthetic services, surely have both the skills and the equipment?

Interestingly I hear Broken Hill RFDS have gone down this pathway (iGel/Ascpe – other services remain with Supreme/FastTrach combos).

Some of the rural theatres in SA have also acquired Ascopes. Like any piece of kit, it’s incumbent on them to understand and train to use it appropriately.

I would NOT advocate playing around with FO for the first time – that would be ‘sporting’. But as a useful defence in a robust airway strategy? Absolutely.

Meanwhile – what do you think of the knife>needle? Counter to Heard’s approach routinely used in Australia?

I think the confusion here is how you define your target audience.

You have described several groups. For some with minimal experience, the best you could hope for is an unrehearsed attempt at an LMA. And as apparently technically straightforward a surgical airway appears, I wonder if human factors will prevent a novice to commit to it if pressed. We know from past experience that even experienced, technically proficient anaesthetists have failed to escalate appropriately in the CVCI situation.

If anything it seems the DAS algorithm is most relevant to the GP-anaesthetist but this still may necessitate a change to the newer LMA variants in their routine practise and engaging in endoscopic training.

If I was trying to achieve maximal impact with minimal training, the first thing I would teach is firstly how to teach everyone how to bag-mask properly, secondly to learn how to insert a basic supraglottic device and lastly how to perform a low-tech, intuitively achieved surgical airway

Only if your proficiency skills were beyond this would I venture to implementing a DAS type protocol.