The South Australian Coroner has just released a report into the sad death of Mr Simos, who died whilst awaiting transfer from a rural ED back to a tertiary centre where he was under a current detention order.

The Coroners report can be accessed here. As with all Coroner’s reports, it makes for salutary reading and in due course I shall add it to the other list of Coroners cases of relevance for rural doctors, over at ruraldoctors.net.

Case summary

The full report can be read online. In essence though, this as a patient whose medical history involved :

- florid psychosis, being treated as a “detained” patient (level 3 treatment order)

- obesity

- COPD

- obstructive sleep apnoea

- poorly controlled diabetes

- hypercholesterolaemia

The patient absconded from an open ward, where he was under psychiatric care in the city. He was subsequently apprehended by police and taken to a rural hospital under existing treatment orders, with a view to being returned to the city psychiatric unit. During the course of this admission he required sedation with olanzapine and lorazepam, and an RFDS transfer was requested. Further episodes of agitation resulted in the administration of midazolam, then respiratory depression requiring assisted ventilation and reversal with flumazenil. Anaesthetic consultation was sought in regard to the pros and cons of intubation; this was deferred as patient was maintaining own airway. Some 12 hours after admission, transfer had still not eventuated. On advice of liaison psychiatrist, haloperidol and promethazine were administered for further agitation. A short while afterwards the patient suffered a cardiorespiratory arrest. The cause of death was undetermined – respiratory depression, agitated delerium and QTc abnormalities were considered and dismissed in Coroners report.

Expert analysis and Coroner’s recommendations

The Coroner made comment of the need for timely transfer of such detained patients from rural facilities to tertiary centres, mindful of the limitations of managing such patients in rural SA. Existing guidelines were acknowledged.

Expert opinion from the CountryHealthSA lead for emergency medicine was not critical of any particular management decisions. There was opinion given that management of such cases should involve

- a structured response (rural doctors, hospital, retrieval service, psychiatric expertise

- a “team leader” responsible for management decisions

- a “flow chart” to guide delivery of care, including assessment, drug use, physical restraint, transport type and final destination

No criticism was made regarding decision to intubate/not intubate, nor use of medications. No comment was made on use of RASS, ETCO2, staffing, availability of airway expertise nor use of alternatives such as ketamine infusion.

Why does this matter?

Such cases are not uncommon in rural Australia. This sad case highlights several teaching points that I would encourage ALL rural doctors to consider, namely :

- familiarity with initial “go to” drugs for managing acute agitation

- assessment of risk of sedation vs exacerbating medical issues (this patient was obese, with OSA and COPD, probable underlying IHD)

- appropriate monitoring

- options for transfer or retrieval

- demands of such acutely unwell patients on clinical staff in rural hospitals and ability to deliver care over a potentially prolonged period of time

The Coroner’s report doesn’t really cover these in much detail – of course in this case appropriate decisions were made and cause of death remains unclear. However I believe that the Coroner’s report could have done more to illustrate appropriate standards of care and to inform other rural clinicians. That it has not done so has prompted this post.

In short, whilst the Coroner has recommended more rapid transfer of such patients to the receiving institution, the Coroner & advising experts have not taken the opportunity to educate rural clinicians on the pertinent issues of safe sedation for this cohort. This man died because of the medical interventions, not because of a lack of transfer.

Typically such patients are unfasted. They may require large doses of drugs for initial control of agitation and all require meticulous monitoring. My approach to these patients has been guided by knowledge gleaned from the FOAMed world, in particular an excellent discussion from the BroomeDocs blog a few years ago, as well as the ongoing work from Dr Minh le Cong and others on psych sedation in rural Australia.

A safe and structured approach to such patients might involve :

- early telepsych consultation and teleconference with retrieval service re: transport urgency and available options

- an agreed plan for both immediate and ongoing restraint

- if using chemical restraint, to carefully consider risks of these agents in regard to unfasted airway, body habitus, cardiorespiratory effects and underlying concomitant medical conditions (anaesthetic risk)

- weigh risks of harm to self/others if agitation not adequately controlled

I like to think of such patients as medical emergencies (akin to a combative or resp depressed head injured patient), requiring full monitoring, including

- 1:1 nursing by an acute care nurse

- pulse, BP, ECG, RR, SpO2

- waveform capnography

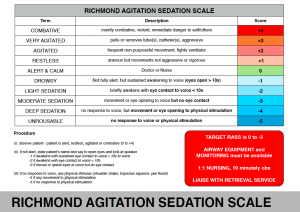

- use of the Richmond-Agitation Sedation Score (RASS)

- immediate access to O2, suction, airway equipment and difficult airway trolley

- immediate access to skilled anaesthetic assistance

- at least two IVs

- consideration of safety for transport including maintenance of own airway vs ETT, and use of safety harness if not intubated

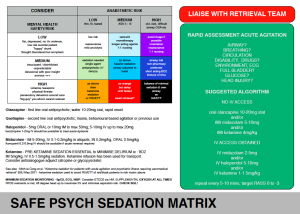

In particular, I would encourage rural doctors to be aware of the PSYCH RISK ASSESSMENT MATRIX (Casey Parker) and the use of KETAMINE for SEDATION and TRANSFER (Minh le Cong et al)

The Consensus Statement can be downloaded from the RFDS website here and I believe should be mandatory across rural SA hospitals.

If you are a rural doctor or nurse or paramedic with responsibility for these patients, please read the Consensus Statement and ensure follow the bulletpoints above.

Not all rural doctors use RASS or ETCO2 monitoring, and often such patients are nursed in a dark environment without immediate access to airway kit, O2, suction.

THINK OF MANAGEMENT OF SUCH PATIENTS AS SIMILAR TO THE MANAGEMENT OF PROCEDURAL SEDATION AS A MINIMUM

That it was not explicity referenced in the Coroner’s report is a missed opportunity – hence this post.

ADDENDUM

Thanks to Minh le Cong who indicates a similar case from Western Australia. There are many valuable lessons from this case, including :

- the value of regular audit of cases in rural hospitals (something I have never seen seen in CountryHealthSA),

- the need for good-quality case notes,

- problems of using Glasgow Coma Score rather than Richmond Agitation Sedation Score

- early and structured use of titrated aliquots of agents to achieve controlled sedation, rather than repeated cycles of agitation requiring sedation in a small unit with limited staffing,

- ownership of the management of such cases, in consultation with local and receiving facilities,

- parallels with the need for expeditious transfer of such patients.

I’ve been pushing for local review of all retrieval cases. Such audit can help drive quality improvement in individual hospitals (not just clinical skills/knowledge, but also equipment needs and of course teamwork/human factors).

Similar audit of anaesthetic ‘near misses’ is practiced in some States (eg: Queensland rural GP-anaesthetists conduct quarterly teleconference audit facilitated by a FANZCA).

Quite why such processes do not exist in South Australia concerns me – indeed, the local lead for rural anaesthesia told me that “there’s no need for audit – we already do this in response to coroner’s cases“.

That’s a classic “wait until the horse has bolted before closing stable door” in my opinion!

Both the SAFE PSYCH SEDATION MATRIX and RASS can be downloaded as PDFs

from the RURAL HOSPITAL CHECKLISTS or RERN ACTION CARDS links.

Consensus Statement – The Acutely Agitated Patient in a remote location can be found at http://healthprofessionals.flyingdoctor.org.au/clinical-resources/?q=cat103%7Cref%7Cformat

I am still a little skeptical about the widening number of indications of ketamine in pre-hospital care. The evidence is fairly slim for those with mental health issues with only some transient benefit seen in those with affective disorders. There is also a suggestion it can worsen the mental state of those with psychosis. If it actually had any useful psychotropic effect then why aren’t we chronically dosing these patients when they are admitted to the ward? Honestly, if the patient has significant co-morbidities that make heavy sedation risky in flight then shouldn’t you just be sedating and paralysing them?

Hello 🙂

I started working as a retrievalist with RFDS this year and I have to say, based on my limited experience so far, ketamine for psych transfer is great. The ability to use a drug that is haemodynamically stable and maintains airway reflexes for someone who only needs sedation for transfer is a great thing.

Whilst I’m not afraid of tubing a patient for transfer, it does present it’s own risks. These are people with often poor dentition, unclear fasting status, they might be obese… There is no capacity for a backup anaesthetist or intubating bronch in the rural/remote settings and if we can ‘risk manage’ our approach by using an agent like ketamine, why not?

Also, Anecdotally, people seem to be ‘waking up’ much nicer after the ketamine infusion is turned off and as the flow chart above explains, oral or parenteral benzos are needed prior to make sure you don’t put a patient in the ‘K-hole’.

Personally, I think if I could, I’d put ketamine in the waiting room water supply 😀

Chris

Thanks for bringing attention to the report and for your comprehensive, educative response Tim. Always a challenge when a floridly psychotic, sometimes aggressive patient presents and needs transfer.

I had a situation once when a brain-damaged patient who had been sleeping peacefully (and was cooperative when awake) woke up at the airport and attacked all of us who were there to care for him. It was frightening and dangerous — probably unpredictable in the final analysis.

Discussion and sharing of knowledge and experience is the only way to prepare for these challenging patients.

thanks Tim for writing on such a significant challenge in rural medicine.

It has been the focus of my research and guideline development in my 10yrs with RFDS . Prior to that I was a rural GP in Riverland, Loxton so I know the area and providers in this coroners case well. I have been in exactly the situation described many times before in that region. What I have learnt during my RFDS career since then, is that we can do so much better.

I respect Peter Joyner’s commentary but would add that as rural doctors and nurses we can do so much more and in fact we need to.

This coroners case bears striking similarities to an early one from WA. http://www.safetyandquality.health.wa.gov.au/docs/mortality_review/inquest_finding/LEE_finding.pdf

The issue of intubation is a vexed one for transfer of the involuntary agitated patient. Its not as simple as paralysing and tubing them. It certainly is not considered the standard of care in hospital and on tertiary psychiatric units…anywhere in the world. You will not find a published guideline anywhere that says that…except now we did publish one in MJA this month that does outline what we believe is the indication to proceed with paralysis and intubation!

As for ketamine, it has a major role now in our RFDS QLd aeromedical retrieval sedation guidelines. It has reduced the rate of intubation for involuntary agitated patients requiring aeromedical transfer ( I am working on a paper right now, describing this)

This is often used in patients with psychosis and we have had no indication ( including from the receiving psychiatrists) , that there is any worsening of the psychosis . The reasons why I think this is so are outlined in our MJA consensus statement.

Suicidal patients will respond better to ketamine than benzodiazepines or antipsychotics. Ketamine has a rapid antisuicidal effect.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3498782/

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25169854

In my view it is the sedation of choice for suicidal agitated patients.

Certainly in this SA coroners case, we know nowadays MedSTAR have adopted the ketamine sedation protocols from RFDS QLD ( they are co-authors on the MJA statement we just published)..so today, this patient would have been trialled on the ketamine infusion if benzos and antipsychotics were not adequately sedating the patient. If that had failed then intubation would have been proceeded to.

I commend the efforts of pre-hospital providers in increasing the evidence base for their practise.

However, the outcomes should not just be related to that of the transfer. For instance, in the setting of multi-trauma I find that ketamine confounds both overall assessment and the assessment of mental function .

I would be interested to know if the impact of pre-hospital ketamine results in lower ISS patients getting a head scan or pan-scanning simply because it is difficult to determine how injured the patient really is.

Hi Derek

Firstly, this thread is not about prehospital trauma

Secondly, if what you mean is how do you assess someone adequately if they are sedated, then this applies for any sedation not just ketamine.The issue is safe sedation to facilitate assessment and management. Its hard to assess an acutely agitated patient regardless !

If you want to discuss trauma, then perhaps start another thread somewhere else?

….leaving aside the issue of ketamine and prehospital trauma (which is indeed best discussed elsewhere eg: http://resus.me/prehospital-ketamine-analgesia/), this post concerns psych transfers.

Turning it on it’s head – it is a HELLUVA lot harder to perform a psych assessment on a M1VTE1 patient who’s been intubated and paralysed….or on a acutely psychotic patient who is tearing up the ED.

Perhaps its better to ensure that there is adequate documentation from referring facility/roadside and receiving facility, as well as documentation of all drugs given, time and response (as was a problem in the Lee case from WA).

Personally I’d rather have a compliant patient, adequately sedated so rouses to voice but is safe to transfer awake without either causing flight risk or needing an ETT

…also could argue that those arriving on ketamine infusion can be gently weaned off the infusion and ‘observed’ in the tertiary centre ED pending medical and psych assessment, rather than clogging up an ICU bed…

Ok. Back to the topic at hand – ketamine in the agitated mental health patient.

I am sitting on the fence on this one. There are certainly sound theoretical grounds for using ketamine but what’s to say that the same outcome would not have occurred even if it was used in the above case.

My issue is that any sedative/anaesthetic/psychotropic requires care in its administration. The therapeutic window can be wide. I have had a little old lady become apneic from 0.5mg IV midazolam all the way to a delirium tremens requiring 60mg of IV diazepam in the first hour just to lie down.

I think giving anything safely is as much the skill and experience of the administrator as the drug. Would you trust a PGY 2-3 RMO without any airway skills following a protocol of administering ketamine sedation to a high-risk agitated patient?

So I will go back to anecdotology,,,,,. A few months ago one of our mid-level trainees tried a little ketamine on such a case. Benzos had not worked and an anti-psychotic had not been tried. I questioned the use in the situation and they said “MedStar use it all the time for transfers and it is the agreed protocol at xxxx base hospital’. There wasn’t much response to the ketamine and we followed up with an olanzapine wafer.

Suffice to say that after about an hour the patient began desaturating with periods of apnea and necessitated intubation and transfer to ICU. The cocktail caught up with him resulting in what some term as a nice balanced anaesthetic. Mind you we work in a tertiary referral centre. No harm – no foul.

There is lots of ways of skinning a cat but my question is who is most qualified to do it?

thanks Derek. thats helpful to know even if anecdotal.

Ketamine isnt perfect and can be inadequate sedation. The MJA consensus statement recognises this and provides guideline as to what to do if failed trial of sedation has occurred. Like I said, my research here in QLD and replicated in Alice Springs, Darwin and Adelaide , is that ketamine sedation has been a useful second tier sedation option that has dramatically reduced the need for recourse to general anaesthesia and intubation to facilitate aeromedical transfer. of the acutely agitated patient .

Make no mistake though,tracheal intubation is still required at times and is the first choice in select patients i.eacutely intoxicated patients

Who is best qualified to provide sedation?in an ideal world,I think it should be a specialist anaesthetist.

Rural medicine is not that world. As this Coroners case highlights, even when anaesthetist was called, he was busy doing other things and so provided only a cursory assistance and left the ongoing sedation to the other doctors to manage. In rural medicine this then spirals into a vortex of psychiatrists on the end of a phone trying to give sedation advice to rural doctors and nurses…not the ideal world of best practice emergency sedation care. ..particularly when the decision to escalate to parenteral sedation occurs.

In essence this is why myself and my prehospital/retrieval colleagues as well as rural colleagues like Casey and Tim, have tried to push for better practice/guidelines. The MJA consensus statement is one avenue that we took cause there was no national guideline providing best practice advice.

So whilst its ideal to think of the ideal, we must remain pragmatic and provide best practice guidance promoting minimum safety standards of emergency sedation to the very providers confronted with these cases in rural and remote Australia

A comment on the protocol: Dosing should be dependent on what has already been given. 1-1.5mg/kg IV ketamine might be reasonable if the patient has had no other sedative on board but I would have trialled for a lower initial dose if I was using it as a second line agent before repeating it as necessary.

My general approach to sedation is divide it into the fully compliant patient to the one who is borderline compliant/uncooperative.

The latter one is the one I usually tend to establish IV access early whether or not their first sedative is oral or IM – whereupon top-ups will tend to be IV until it is shown they are agreeable to oral. Of course those who are initially compliant on oral medication but then escalate will also be the ones I then switch to an IV strategy.

I definitely understand the difficulty of rural practise and infrequent exposure to specific scenarios. I would be just as apprehensive at doing a lateral canthotomy, blind burr holes or resuscitative thoracotomy – and I work in a major trauma centre

And sometimes it isn’t the doctor’s experience which is just limiting, you need good support staff that know how to observe, monitor and respond. The problem is as much in the tertiary hospital wards where staff can do de-skilled at managing even a moderately unwell patient that they end up needing to go to ICU/HDU.

Being mindful of that my general rule of sedation:

1) IV is the best way

2) Fake high, shoot low

3) You can always give more but you can’t take it out

4) KISS – the more you mix and match, the less predictable the response (that includes whatever the patient has already taken)

5) Always do it in with proper monitoring and ideally 1:1 special

6) The first hour is the critical period. If anything amiss they need ongoing close monitoring or you need to transfer to somewhere that can

7) If all of this consumes too much of your resources, make it somebody else’s problem e.g. ICU, Medstar (you have better things to do)

8) And politely tell the city psychiatrists that you aren’t taking their guidance about acute sedation (they are generally the least qualified to give it).

I hear you – but argue (passionately) that the DISCIPLINE of rural practice means we HAVE to be able to do this stuff. Just had an email from a rural colleague who was appreciative of this commentary – because it’s such a COMMON scenario….

…however, my beef s that the finesse and safety around providing safe sedation is off the radar to a degree – which is why I laud the efforts of people like Casey (for his 2111 safe sedation matrix) and Minh (for ongoing work with safe transfer).

Whilst it’s appropriate to “make this someone elses problem”, rural docs (and the nursing staff) need to make sure they can do so safely.

Having just spent 6/12 with MedSTAR, am struck by the heterogeneity between rural hospitals – some are outstanding, some are not – it’s usually the docs that are weak links (locums, old school etc) OR the lack of institutional protocols. Sedating these patients is potentially risky and I think the discussion here highlights aspects to consider. Shame the Coroner didn;t mention in the report….

You can lead a horse to water…..

Do you see any patterns in this heterogeneity? Well written protocols are a good starting point. But as you say if you have apathetic leaders then I wonder what happens. For want of a less cliched word, you need a champion in each institution to drive this change. Old school practitioners, FIFO docs and undertrained grads won’t be the ones that do will do this. And don’t get me onto the trite rhetoric of so-called rural medical schools……..

Remember that people of the KIDocs, Pharm and Broome Docs persuasion are unfortunately rare. You care about the quality of your job, you aren’t deterred by the challenges, you seek practical solutions and want others to share your passion. In other words you want to raise the bar in a general manner. The Coroner just wants to cater to the lowest common denominator.

But the problems that are outlined occur just as much in the ‘big smoke’. Consider a couple cases last year of high-risk patients undergoing major surgery in a metropolitan private hospital.

http://www.courts.sa.gov.au/CoronersFindings/Lists/Coroners%20Findings/Attachments/581/RYAN%20John%20William%20and%20WALTON%20Patricia%20Dawn.pdf

I admire you for your passion and I hope that others will embrace it. But some just don’t want to know and don’t care and the best and only option is for them to feel free not to cope.

By the way I am still trying to find a time for you to speak to our trainees to show them what the real world looks like.

Fair call Derek…

The heterogeneity issue in rural bothers me immensely. Your points are well-made and capture the issue fairly well. My experience (and it is of cohrse anecdote) is that generally the nursing staff in country hospitals are constant and know what “needs to happen”, whereas the MO quality is variable.

Like it or not though, the skillset required of a rural clinician means they MUST be able to deal with this sort of stuff, safely. Parachuting a city-trained GP into Woop-Woop is unfair on rural patients, staff and the clinician…

I’ve heard it said that “better a bad doctor than no doctor” in rural areas…something ai struggle with. By all means support these areas with excellent reteieval services and aim for rapid transfer of sick patients ASAP (including those psych patients on a treatment order)….but also need to ensure a safe competency in sedation, airway management and EM skills. We have the nursing staff and the kit (mostly)….just need to ensure the ‘minimum standard’ is raised from ‘deliver BLS and call for help’ mentality to ‘deliver appropriate timely care and facilitate transfer’

It is do-able, but requires leadership and support. I still beleive the Coroners report in this case missed an opportunity to educate and indeed encourage appropriate standards for such cases….

Its not all about ketamine! Great discussion, thanks all…

Thanks Derek, Chris, Janelle and Minh for comments.

Just to reinforce – in the isolated rural hospital, with an occasional intubator, limited staff and an unfasted, obese ptietn with OSA/COPD/IHD, intubation is not without risk.

Ditto repeated cycles of agitation-sedation.

The key (as always) is minimum necessary intervention. A calm relaxed environment. good supportive nursing. Ensuring patient dignity. Excluding (or at least allowing for) intoxication, head injury, agitated-delerium, nicotine withdrawal etc. Ensuring an empty bladder….removing clothes and placing in a gown (ensures no hidden weapons, drugs or belt/laces etc to cause self-harm)

For those faced with such situations, rapid control with an antipsychotic or benzo and titrated doses…using RASS to achieve minimum level of sedation for control….in an environment that, whilst calming and secure, allows immediate access to O2/suction/airway kit.

Rapid transfer of such patients, where possible – mindful that 1: nursing depletes a small rural ED of about 50% of it’s staff…and that the longer such transport is delayed, the greater the possibility of ongoing agitation-sedation cycles or missing pathology (the agitated patient with an occult head injury is a classic example)

Ketamine has a role – I’ve seen it turn aggressive 110kg patients in extfreme agitation from “miaow-miaow” into pussycats, able to be transferred by road or air, in an appropriate RFDS safety harness, to destination and avoid risk sof unfasted intubation in remote location with attendant risks.

Of course, if control of agitation is not possible OR if concern of over-sedation, then by all means secure the airway.

The consensus guideline mentioned in the post from Le Cong and colleagues is a step in the right direction…and it is a great shame that this was not mentioned by Dr Joyner or the Coroner, as there are really valuable lessons over and above those cited in the SA and WA reports, of relevance to rural docs….

I want to highlight the issue of emergency sedation in rural hospitals.

Casey Parker has raised this previously on his blog and I know he is trying to improve things in his neck of the woods with consensus guidelines locally

the fact is we dont do emergency sedation well. its not well taught and its not well studied and certainly not well governed/audited.

this coroners case highlights the need to regard emergency sedation as a FORM OF ANAESTHESIA.

Once you start using IM/IV sedation, it really should be treated like an emergency anaesthestic with all the minimum safety criteria, monitoring and appropriately skilled providers in attendance.

It is notable that in this coroners case, the anaesthetist called, recognised the risks of intubation in a patient who was stable but then it was left up to GPs to manage the emergency sedation which likely contributed/led to the fatal outcome. It is even more notable that the patient required rescue reversal medication from IV midazolam and then was still monitored in a general ward with general staff. This is why in our consensus statement that once IM/IV sedation is required, it should be done in a monitored resuscitation area with at least one trained provider who can provide advanced life support and airway management.

Furthermore, our goals of emergency sedation are often vague and ill described. WE do not have an objective level of sedation that is targetted when giving oral/IM/IV sedation. This is why in RFDS Qld and in the consensus statement we strongly advise use of a validated sedation scoring system like the RASS.

The definitive care of this patient was not going to occur via aeromedical transfer. The definitive care was to provide safe sedation and reduce his arousal state/agitation.

This is an important point. Unless you are frequently doing this, it is difficult to judge the continuum from light sedation to full anaesthesia. The approach should be the same. But this is why interns generally under-sedate the delirious patients on the ward and psychiatrists believe midazolam kills people.

IV titrated sedation, objective scoring systems and close clinical/physiological monitoring are all required to achieve this safely. I don’t think I have ever ended up with an apnoeic patient by following this. It is far more dangerous when patients are given an empirical IM shot and thrown into a padded room for the medication to take its effect.

Agree 100%. That is whole point of this post – safe sedation, appropriate risk assessment, use of RASS over GCS (the latter predominates in the discussion of Lee case in WA) and need for all the appropriate kit – O2, suction, airway kit and training, plus ETCO2 etc etc. The FOAMed posts from Casey and Minh in past few years are great FOAMed to inform rural practice, and the Coroner’s case doesn’t really cover them, which is a great pity.

THINK OF MANAGEMENT OF SUCH PATIENTS AS SIMILAR TO THE MANAGEMENT OF PROCEDURAL SEDATION AS A MINIMUM STANDARD

…then work on getting them out safely.

A patient undergoing an anaesthetic procedure is more likely to be transported than one who is not…be clear though, I am not advocating giving sedation or whacking them onto a ketamine infusion or ETT/IPPV purely to expedite transfer. That would be…..naughty!

I presume these are not widely available rurally but we have these specially designed nasal specs which have a ETCO2 port to semi-quantitatively monitor ventilation in spontaneously breathing patients.

I honestly think this is one of the greatest inventions for the past several years.

They are available…and better still, compatible with the Phillips MRX defib-monitor in most rural EDs and the current Zolls used by MedSTAR. Indefensible NOT to use ETCO2 IMHO

If doing this sort of work, need the right kit….and training….and mindset.

Shame Coroners report didnt delve a little deeper and make more useful recommendations for benefit of rural clinicians and their patients….

So rare for the Coroner to completely miss the point.

We also require good leadership from within CountryHealthSA – to my mind this topic is one for both the lead in emergency and in anaesthesia to comment on – both rural docs. Peter Joyner’s input is useful, but perhaps could have done more.

Sadly there is a bit of a leadership vacuum in rural – which may be reflected in standards of practice “out there”

My interest – and that of Casey, Minh and others – is to deliver “quality care, out there” – FOAMed helps.

Derek, at 0400hrs, as the on call doctor in a rural ED with just 1 nurse and 1 midwife to control the 100kg Amphetamine intoxicated patient who is destroying your emergency room, Ketamine will save both your own and the patients life.

A stat dose followed by titrated infusion is simple/safe to use and will rapidly settle both the mad and the bad.

As a bonus you will never turn a “pink” patient “blue” with this drug, something that you are at high risk of doing using other drug combinations in intoxicated persons.

Rural ED’S are a dangerous place for psychotic or intoxicated patients, Ketamine use will reduce this danger by a huge margin,

If you need convincing, feel free to do a couple of night shifts with me, you can make the call on what sedation we use after you have watched me use Ketamine on the first mad / bad patient for the night.

Interesting perspective Bill. In rural we are often hampered by lack of available hands to help…the Dr-RN-MW combo is not uncommon!

Rural ED is definitely an unsafe place. Cautious titration of agents may well be option of least harm, but of course requires full monitoring as if performing an anaesthetic…not being loaded with Oral, IM, IV agents then left in a dark room unmonitored with an EN doing hourly obs….

Agree 100% that quick takedown then switch to lowdose infusion can increase safety margin hugely for these patients…but still treat as if giving a GA….we dont want people to think a ketamine infusion is a ‘set and forget’ – requires full monitoring, RASS, ETCO2 and a plan for retrieval ASAP…

Encouraging this as a standard across rural would be a good thing, we agree!

Bill, I am not trivialising the issue when you all you have are three HCWs and no Chubb security in sight. My priorities would always be staff safety first then patient.

If you know what you are doing and have the staff and resources to administer the intervention and monitor the patient I don’t particularly care which drug you give. My only caveat as I said is that a sedation cocktail is always going to be less predictable in its effect than using a single agent. That seems to be evidence from the case reports of deaths from recreational ketamine use.

Any protocol that is developed is clear enough that it can be safely followed by someone with reasonably little experience. I have a problem when some cowboy resident attempts something based on a misinterpretation of an Internet post and think they can replicate the results of an expert.

We don’t need another Conrad Murray giving a MJ special.

One of the greatest dangers of FOAMed is for unaccustomed readers not understanding context. If you have the fundamentals right and already a safe & prudent doctor, it is a great resource. For others maybe they need to get back to basics.

Indeed. Same could be said for reading a recipe from textbook.

The KEY here is about safe provision of appropriate minimal sedation (rouse to voice, ideally) by isolated rural clinicians…..not just expediting transfer as indicated in Coroners report.

Rural clinicians in the bush using FOAMed to improve practice? Yes please.

Unsupervised 2nd year RMOS doing something they read about on the net? You need to supervise them better in the tertiary ED!

Tim,

To that end, whilst FOAMed is a useful part of the education strategy, what do you suggest as additional resources to disseminate information and practically support rural clinicians in their professional development goals? And what specialty colleges and your more resourced colleagues in the city can do to help?

Tim, I dream of being left in a dark room with an EN doing hourly obs and I am sure that some of my patients would be happy with this result in lieu of punching the daylights out of a couple of policeman who then return the favor and Tazer you into a semiconscious state, all this as a result of Olanzapine / Diazepam escalating your behavior.

..I think it HAS to come from within – strong leadership within CHSA would help.

we also HAVE to get away from the idea that “any doctor better than no doctor”. If we are stuffing up in rural, we need to have the feedback….in a constructive way. Ideally it begins locally though, with a desire to want to be better, not just refer on or let medSTAR come and fix the pain…need to fill the therapeutic vacuum. Not trying to be hard on rural – it’s a tough gig, struggling with infrequency of critical illness and problems of staffing/kit – but that’s the gig, so have to be able to deliver despite that. There are beacons of excellence out there in rural….but also some places that aren’t. Dragging the bell curve to the right is my aim….

Some lessons from interstate – regular case audit of cases transferred to tertiary perhaps, where near miss or scope for improvement – a phone call is ideal…or a facilitated discussion via FACEM via teleconference as a group session. Local champions – definitely. Funding and silos are a problem…

A quarterly anaesthetic audit via teleconference with FANZCAs is standard in Qld I believe, for the GPAs. No reason couldnt do here….

Definitely local audit of ALL retrieval cases to encourage improved consideration of local needs (knowledge, equipment, human factors etc). I think this is essential and acts as a focal point for quality improvement in less critical cases in the rural ED…

There has been an incredible improvement in cardiac care via Phil Tideman and co’s efforts with iCCNet. 24/7 phone advice for ECGs and ACS patients. I’d love to have same for trauma radiology – we have digital imaging, but no means to send an image other than ring the relevant reg and take a screenshot with smartphone then text it! Would be ideal to just be able to email images to eg RAH trauma reg for advice if needed, 24/7 like iCCNet….

We should talk…

the irony is that we have known about this issue for a long time. officially, at least 10 yrs by this October

http://www.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-n-safety-toc~mental-pubs-n-safety-3~mental-pubs-n-safety-3-saf

safe transport of mental health patients is a key issued identified in the National paper on reducing harm in mental health care, 2005

This is why I think the Transforming Health implementation is disempowering to smaller sites. There is an overemphasis on concentrating resources for ‘high-end’ services which have only marginal increasing benefit to population health indices at the expense of improving the overall standard of dealing with common problems. Coupled with this is this idea that ambulance and Medstar will solve all the health access issues of ‘non-super’ sites not only in rural sites but also regional centres in the metropolitan area.

This is all a movement to ‘dumbing’ down the overall standard that can be provided by those outside of a major referral hospital.

The exacerbating factor is that the health system is so inefficient and fragmented. Despite our 21st century interconnected society, it is still difficult for remote practitioners to obtain timely and accessible advice from specialists. There is no direct hotline and not infrequently you end up with a snotty registrar dispensing questionable advice with no understanding of the context or resources of the referring doctor.

Also means the retrieval service becomes more of a non-acute transfer service….

I guess these people still have to go to town….they cant be fixed locally. But we need to ensure rural docs can deliver the goods until retrieval arrive.

Therapeutic vacuum and all that….

A metrocentric approach and running cou try services i to the ground will cost more for marginal gains…

When the service is irrational be sure to know that it is always rational to those who wish to maintain or increase their power and influence.

Pingback: PHARM Podcast 114 : The Aikido of emergency sedation | PHARM

Pingback: LITFL Review 174 - LITFL

Just found this interesting discussion via the PHARM blog. I do some event medicine work in the UK at music festivals and we regularly get between 2 and 10 acutely agitated patients per shift who have taken various recreational drugs. They tend to get to us restrained by 4 or more security staff or sometimes we go to them when they are so agitated that security can’t move them at all.

The RASS 1-2 ones are generally ok and best managed with oral meds (Benzo/Haloperdiol). Some of the RASS 3-4 patients are clearly going to be OK with little benzo, either 2mg Midazolam IV or 5mg IM with 5mg Haloperidol.

We do get some however who are a real problem. One a few days ago had taken 800mg of MDMA plus ketamine plus cocaine plus LSD plus alcohol. He came to us fighting 8 large security guards and had already bitten 2 staff members. He had IV access established and 5mg Midazolam IV repeated twice with absolutely no effect – still RASS 4 and fighting successfully 5 minutes after the 3rd dose. I suspect these are the people that ketamine is probably useful for and it’s just been added to our formulary for patients that are still combative after 2 doses of Benzo. We do have the luxury of 2 paramedics/nurses per patient in our resus beds though so monitoring is straightforward compared to some rural settings.

Pingback: Surviving Sedation Guidelines 2015 | PHARM

Pingback: Got droperidol? - KI Doc

Pingback: LITFL Review 174 • LITFL Medical Blog • FOAMed Review