If you’ve been following blogs such as THE PHARM recently, you’ll probably have seen reference to a chap called Minh le Cong and a drug called ketamine. Now it’s no secret that many in the prehospital and emergency fields are fond of ketamine – it’s a useful dissociative agent with analgesic properties and can be given IM, IV or IN and used for analgesia, sedation and induction.

Like any drug it requires familiarity with use and titration to effect (although I prefer pre-drawn drugs for RSI, with doses based on IBW and haemodynamics). I reckon that if I polled a roomful of doctors and asked them to give a dose of ketamine, many would be hesitant having not used it before. Safe practice mandates familiarity with the drug and appropriate training and monitoring…

Sedation of the Acutely Agitated Patient – a High Risk Procedure

But there is an area of practice that has bugged me for some time, namely the management of an acutely agitated patient. This is a difficult situation – the patient is agitated and may be a risk to self and others. The staffing in a rural hospital is minimal – there is no ‘Code Black’ with security officers – the team may involve an RN and EN initially, with the on-call doctor off site and taking some time to arrive.

Whilst a calm environment and de-escalation is ideal, sometimes situational urgency mandates use of agents to calm the patient. It’s all well and good if the patient is cooperative and insightful enough to take a dose of oral medication (typically olanzapine antipsychotic +/- oral diazepam)…but if not, they may require a rapid ‘takedown’ with IM or IV medication.

And this is a problem, as the agents commonly recommended by many Health Department protocols STILL include short-acting agents associated with profound respiratory depression. Alternating cycles of extreme agitation, and administration of short- and long-acting agents can lead to increasing amounts being used and a slide into respiratory collapse.

Looking few various protocols from various sources can be confusing; there’s a wide variety in suggested agents – a quick search in an (unnamed) rural ED showed a variety of available protocols. This is potentially dangerous – in a crisis, the ‘occasional sedatonist’ is likely to seek some form of protocol..and yet may lack familiarity with the agents in use.

The Occasional Sedationist may be reassured by a protocol and lulled into a false sense of confidence in administering drugs without adequate backup

Many protocols seem to encourage polypharmacy, including the use of IV midazolam. Other agents in some of these protocols include ;

- ORAL olanzapine, diazepam, lorazepam, risperidone

- IM olanzapine, haloperidol, clonazepam, midazolam, lorazepam zuclopenthixol

- IV midazolam, diazepam, lorazepam

Even though there have been recent Coroner’s reports on deaths of such patients, a recent report failed to address the issue of safe sedation and instead focus on the need for more rapid transfer. Whilst I am in favour of rapid transport of patients requiring retrieval (not least because of the demands on staff in a resource-limited environment), it’s not the lack of a helicopter that kills these patients – it’s the cycle of agitation-sedation and cardiorespiratory collapse, occasionally exacerbated by restraint that is dangerous. Couple this with a general failure to approach the clinical situation with the same diligence as we would for providing procedural sedation in ED or OT, with it not unheard of for these patients to be nursed in a dark room, supervised by a mental health worker outside the door, with occasional recording of routine obs – scant appreciation of the fact that we are giving administering anaesthetic agents!

Moreover, many of the protocols available in EDs make vague reference to ‘safe environment’ without specifying the need for airway equipment, the use of ETCO2 to monitor nor airway or anaesthetic risk assessment.

Pertinent Coroners reports are here :

Adam Fernandez Coroners report

Droperidol & ketamine – safer than short-acting benzos!

So the Twittersphere was abuzz today with the announcement of the DORM-2 study from Melbourne – a prospective observational study looking at the safety of droperidol for management of these patients. Older readers may remember concerns from 15 years or so ago regarding droperidol and prolongation of the QTc causing torsade de pointes. The study demonstrated no prolongation of the QTc in the cohort studied, nor any incidences of torsades de pointes (a criticism is that this is relatively rare and would require a larger study). More importantly, the study demonstrated the effectiveness of droperidol in achieving a state of rousable sedation – the goal in this situation.

I think this is important. I use droperidol occasionally in theatre for both sedative and anti-emetic properties; it’s available in most hospital or can be ordered in. And I think it’s a useful addition to the armamentarium. So much so that I’ve dropped haloperidol from my approach and will run with initial olanzapine where possible; if this fails, IM droperidol titrated to target sedation score.

Of course ketamine DOES also have a role; and I am a particular fan of it’s use for transport of such patients without the need for risking RSI in an unfasted patient with unproved airway (obesity, OSA and COPD are not uncommon in these patients, as are complications of intubation such as aspiration and the need for an ICU bed at the other end). There are protocols available for running ketamine infusions once initial sedation is achieved. I won’t reproduce them (for examples see here and here), but suggest that early consultation and advice from the retrieval service is mandatory…

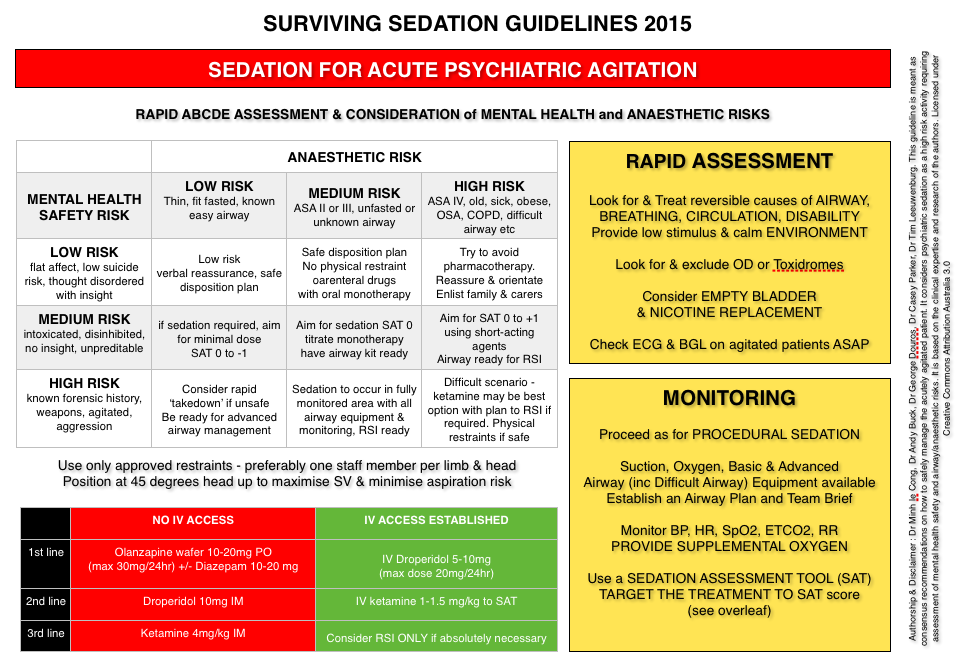

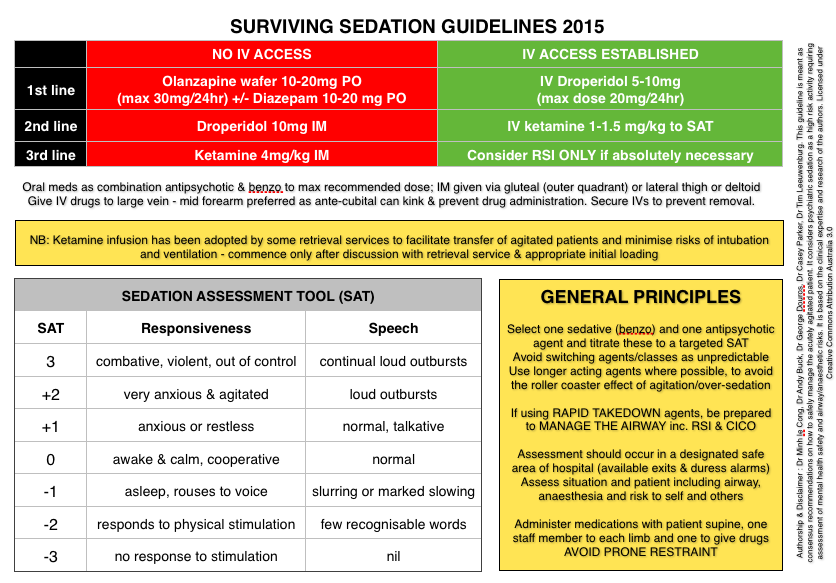

Safe Sedation Guidelines 2015

Moreover, it helps bolster a rationale approach to sedation of the acutely agitated psychiatric patient – there’s been a bit written on this recently, with release of a Consensus Statement – The Acutely Agitated Patient in a Remote Location as well as a collaborative effort between some emergency and rural clinicians in Australia to guide practice in rural ED or on the wards.

We’ve termed it ‘Surviving Sedation Guidelines’ in recognition of the very real risks that use of these agents can pose.

Listen to a podcast here on the “aikido of emergency sedation” from Minh, Casey and myself

See also posts on Surviving Sedation Guidelines 2015 from the PHARM here, from BroomeDocs here and from KIDocs here

KEY PRINCIPLES OF SURVIVING SEDATION GUIDELINES

Early Goal Directed Sedation (EGDS) – titrated sedation to an objective level using a validated sedation scoring system

Consideration of emergency sedation as a form of procedural sedation/anaesthesia.

Minimum standards of patient assessment, resuscitation equipment and clinical monitoring

De-emphasis on sedative drug choices with more emphasis on continuous clinical assessment and titration to effect

There is a lot more to psych sedation than just bunging in a dose of benzo and walking away…I’d encourage people to read the extensive notes on Minhs blog post regarding this, and consider the use of droperidol, as well as stalwarts olanzapine and diazepam in a stepwise approach titrated to a desired sedation level.

Other than oral diazepam, there is no mention of using short acting benzos such as midazolam…and I think this is a GOOD thing! See what you think….

An updated version of the guidelines is here: SSG2015v6

thanks Tim for tidying up the SSG15 guidelines. Looks fantastic

One point of difference between V6.0 here and the V4.0 that we originally released is in haloperidol as you point out.

I wish to outline why I still advocate for use of haloperidol in acute sedation if droperidol is not available.

1, There is RCT evidence in acute situations that droperidol and haloperidol at equal dosing, provides similar sedative effect in majority of cases used. Here is the citation:

Droperidol v. haloperidol for sedation of aggressive behaviour in acute mental health: randomised controlled trial. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25395689

2. Haloperidol is widely available especially in other countries like USA, Europe and Canada. Rural Australian clinics and hospitals do not always have droperidol but almost all have haloperidol due to its long safety record and experience.

3. Haloperidol is listed as safest sedative agent for agitation in setting of acute intoxication especially from alcohol.

Consensus statement here http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3298219/

I respect though your opinion here Tim and do agree that if droperidol is available or can be sourced then it is a superior agent. However as per the Isbister RCT, it is also equally good choice to use haloperidol.

regards

Minh

Yes, thanks Minh – haloperidol remains widely available and equally effective. Should add the need for benztropine availability with these agents…I’ve gone with droperidol cos I use it in OT and am quite happy to extend to ED/wards….

Should also mention that haloperidol is also available in PBS Doctors Bag supplies and most rural EDs, so dont chuck it out with the midazolam!

I’ll see if can re-jig the SSG to allow the option of stalwart haloperidol, OK?

tim