I never used to have much to do with paramedics as a junior doctor. It was only when working in the ED as a registrar that I was exposed to them…probably a good 3-4 years into my postgraduate medical career. Even then, I had little idea of the challenges they faced, despite being in the same business of managing trauma, critical illness. But of course with the usual pressures in ED (access block, running at 120% capacity, begging for appropriate consults and dealing with all the usual stresses of staffing and supervision) it was easy to just bemoan the fact that patients were dropped off covered in gravel from the roadside and possibly some time after the incident.

In short, as an ED reg starting off, I had little idea of the challenges posed by the prehospital paramedics. And it was easy to criticise. If that was my mindset, just think of that of the rest of the hospital! Nothing could be further from the truth. Fastwind forward a decade. I’ve spent a lot of time in medical education, instructing (and directing) on the international ‘advanced trauma life support’ aka ATLS (EMST in Australasia). In fact the full name of this course is “ATLS Course for Doctors” – it remains medico-centric and is a product of the College of Surgeons it is no secret that I am a critic of this course- it fulfils a need for entry-level, but doesn’t really deliver modern trauma care, hence the proliferation of other course such as ATACC and ETMcourse.

The usual stereotypes of (shudder) just ambulance drivers no doubt predominate in some medics mind when I trained … and I suspect this attitude still exists, as some of my paramedic mates refer to themselves (self-deprecatingly) as ‘just an ambulance driver’. So along my postgraduate career and in time as a medical educator, I have tried really hard to do the following :

- to understand and explain to doctors who I train about the valuable skills of paramedics/prehospital

- to seek to break down traditional silos between different providers, such as paramedics and medics

- to use simulation training to improve delivery of care in resus

My mission continues – part of the reason I am rotating through medSTAR is to pick up pearls from prehospital care, simulation and standardisation of training, as well as case audit and governance. Even as a seasoned doctor, I make an effort to go on other courses relevant to resus – some of which are geared specifically towards the prehospital environment (eg; STAR). But it is still rare for medics to cross train with paramedics and see how they do it.

Enter the Sim Environment…,

So I was delighted to be offered the chance to attend some of the sim training for graduate paramedics commencing their internship. This program is an intense three week course of lectures and scenario testing for the intern intake, designed to help equip term before “hitting the road”.

I was only able to make it for one day – but can report that I was blown away with both the quality of simulation delivered AND the clinical skills of the paramedic interns. My host was former nurse and current paramedic educator, Michael Borrowdale.

Michael proudly showed me around the SA ambulance training facility (refurbished office spaces) which were cleverly kitted out on a shoestring budget to mimic indoor environments including patient homes, nursing home, resus room and crew room/stock cupboard. Furniture was sourced from donations and clever use of curtains to change wall appearance allowed the same room to function as a bedroom or a resus, bay, a bathroom or a lounge room. Cheap video cameras from DickSmithElectronics allowed recording of the scenarios to linked PC, for under $100

Attention to the little details adds to the fidelity of simulation – having webster packs, ID cards and the like adds valuable clinical information (organ donor, medications). And for immersive sim, use of sight, sounds, and even smell contributes hugely.

I watched four different sims, each run in ‘real time’, requiring the candidates to manage the condition from arrival to disposition, with varying levels of complexity. Use of a mix of live patients and mannikins, along with students role-playing relatives, nursing staff or police officers added to the realism and encouraged skills in scene management and situational awareness.

I was impressed that candidates had to manage the scenario from arrival and initial assessment, maintaining communications with HQ, instituting immediate management, calling for backup, dealing with distressed relatives, environmental concerns, extricating the patient, dealing with unexpected crises (sudden desaturation), loading patient, transporting via ambulance and handover to ED.

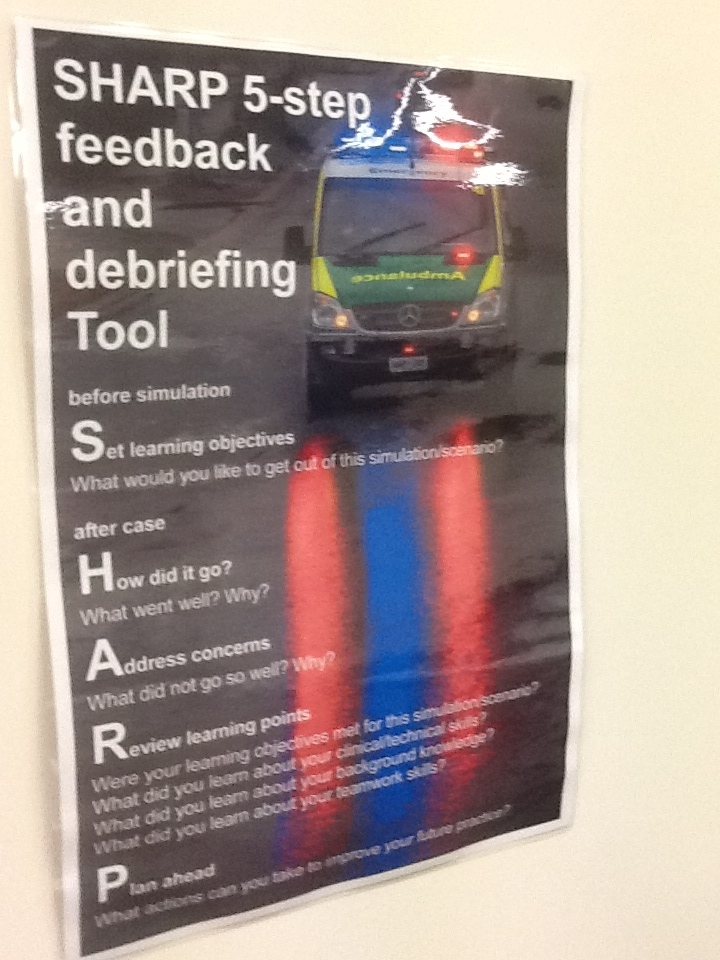

Each scenario ran for about 30-45 minutes and was expertly debriefed by experienced facilitators with plenty of roadcraft experience. Crews were split and sim continued even after patient departed, with remaining crew having to clean up, deal with relatives/media/police and both teams write up case cards.

The realistic prehospital scenarios, carrying a significant cognitive load in not just clinical management but scene awareness lead to a degree of stress inoculation.

Despite being involved in running trauma sims via ATLS/EMST, running my own ‘guerilla sim’ and attending other courses in resus/prehospital care here in SA and interstate, I can say that I have NEVER seen such a high level of immersive simulation. Sight, smell, sound and sheer cognitive overload from various players (distraught relatives, police, press, carers and assorted players created a level of sim I’ve never experienced before)

Throughout this, the paramedic interns displayed effective clinical skills and excellent crisis resource management.

“To put it bluntly, I have never seen this level of immersive simulation in ANY of my medical career, despite running and attending sessions focussing on resus training. Nor have I been privileged to witness the level of clinical skill displayed by the paramedic interns at such a junior level”

After witnessing this sim training, I am fully confident in the skills of the paramedic interns – as they progress through the ranks, skills will be further fine-honed. I hope that other prehospital workers, whether career crews in metro or volunteer crews in rural, will be able to undertake the same exposure of sim training.

I could not help but reflect that I wish that doctors had access to the same level of immersive sim – in fact, one could argue that even established senior doctors would benefit from participating in such well-organised, immersive and stressful simulations – rather than the usual token ‘stop-start’ sim. This applies whether preparing for prehospital work or for ongoing training in hospital-based work.

Recommendations for the future?

People may not be aware, but the number of graduate paramedics churning out of university each year vastly exceeds the number of available spaces. Unemployment is a real possibility for these graduates. Even the interns who do get a spot are only secure for a year – they are not guaranteed a longterm position and many seek work interstate, overseas or in other industries (mining, oil rigs etc). Meanwhile rural areas are mostly dependent on (unpaid) volunteers, trained to a Cert IV level but lacking skills such as cannulation etc. Not an easy balance between affordability, case load and number of graduates to positions.

I don;t have an answer for this!

But if we are serious about clinical training, I think we need to get away from tokenistic, task-trainer focussed sim or ‘tick box’ annual ACLS updates, moving instead towards highly immersive sim delivered in real time, using realistic scenarios backed up by actors, and use usual equipment. An ideal training facility would be co-located with emergency services, allow cross-training with other agencies (paramedics, medics, retrieval, fire service, SES etc). Ability to deliver sim to outlying sites would be useful.

But ultimately, Michael Borrowdale and colleagues prove that one can run highly effective, fully immersive simulation on a shoestring budget, with fully realistic sound, smell, touch and the cognitive stressors of scene management including dealing with highly distressed relatives, environmental concerns (rain, cold, sun) and from scene arrival to patient delivery.