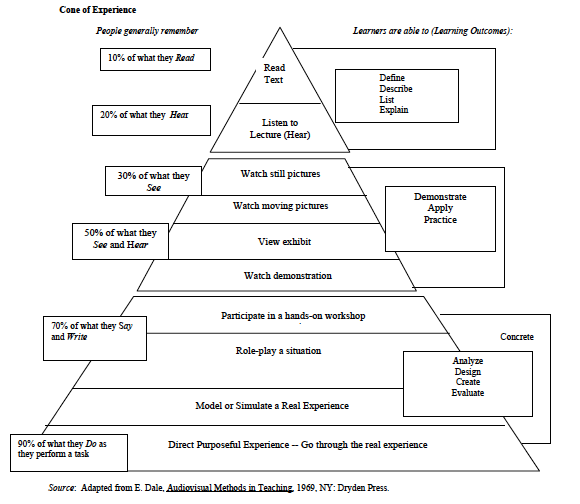

I’ve recently had cause to re-examine Dale Edgar’s ‘Cone of Experience‘. Like that fabulous educator from iTeachEM, Rob Rogers (@EM_Educator), this concept seems intuitive and demonstrates nicely the benefit of learning via different formats. I use it in talks to explore different learning styles.

Except it’s bunk. Dale never ascribed percentages to the retention rate for each different mode of learning; rather the ‘cone of experience’ demonstrates the varying abstraction potential for each learning mode. Understanding that Dale’s model was centred around understanding the concretness of different material, not retention rates.

Why is this important? Because it’s not uncommon in medicine to come across the view that “there is only one correct way to do X”

When I was a junior, following such rules made sense – they reduced the burden of having to ‘think’ too hard … and when such rules were imposed from a higher authority (invariably a gruff Consultant), failure to comply risked raising their ire! Of course it’s not just lack of years or having a steep authority gradient that encourages sticking to such rules. As humans we tend to seek the comfort of familiarity and our own experience when making decisions – hence the “I’ve always done it this way…” or “Textbook X (authored by eminent expert Y) tells us to do it this way, so I’m sticking with that…” or even the “The teaching is to do procedure X this way – anything else is negligent” conundrums.

Nowadays when someone asks me how to do something, I seem to find myself pausing more and more as I reflect on previous experience. No longer do I say “Chest drains? They’re easy, let me show you how” – instead I pause “Well…it can be difficult…let’s talk about it, then I’ll help & guide you through one” as I recall not the vast majority of easy ones, but the difficult cases, the errors made, the complications…and am keen to relay this tacit experience bro e through mistakes to my colleague.

Some recent debates on social media have been relevant. Over on doctors.net.ukfora, we’ve had examples of :

– experienced clinicians ‘told off’ by physios for eliciting lower limb reflexes in a seated patient “the ONLY way to do reflexes is with patient laying down”

– anaesthetists laying into emergency physicians over options for safe sedation of the haemodynamically compromised patient in VT (with the usual cliched ‘needs RSI‘, through ‘mustn’t use ketamine because of strain on heart‘ through to ‘just zap them and apologise‘). Kudos to Cliff Reid & Ed Valentine for keeping their cool in that debate!

Meanwhile there’s been a useful Twitter and Google+ exchange on dogma around use of femoral traction devices (FTDs) for splinting of femoral fractures in the presence of a pelvic fracture

There are plenty of other discussions that crop up – cricoid force, checklists for crisis, thrombolysis in stroke, acceptable modifications to RSI etc etc

In all of these discussions, it’s not uncommon to see people looking for “rules”. In the recent examples,

– physio wanted a rule that all lower limb reflexes are elicited in supine patient

– anaes colleagues wanted to use propofol RSI for the patient in VT and berated use of ketamine

– traditional teaching is to avoid use of FTD in presence or suspected presence of pelvic fracture; some paramedics were lookign for guidance on rules whether to use a FTD or not. Wise words from experienced paramedic/retrieval practitioner Dave Tingey “clinical judgement is the key – especially where there is little or no evidence” – he emphasised focussing on patient outcome, not rules for a process!

FOAMed – tacit knowledge sharing with global community

People ask me why I use social media for learning. For me the attraction of FOAMed is that it addresses the issues where there is clinical uncertainty. If you are looking for absolutes (as when learning the craft of medicine or to pass exams) then stick to the textbook teachings. If you are looking to test yourself and continue to explore the expanding frontiers of knowledge, then use FOAMed. It opens up the world of #dogmalysis and enables corridor conversations with clinicians worldwide. Some of what you encounter is bunk…some is golden. The trick is to filter, engage, question and unlike politicians, don’t stick to one party line.

Even if “the more you know, the less certain you are!”

Guessing PM Abbott would not be amenable to uncertainty