Last year I was amazed to discover that over 50% of my rural GP-anaesthetic colleagues stated that they had been called out to some form of prehospital incident in the previous 12 months. I think we need to be very clear that the pre-hospital environment is VERY different to that of the resus bay or ED, let alone the operating theatre or consulting room!

The experts in prehospital care are the State-based paramedics and retrieval services; indeed we should all be agreed that this is no place for ‘enthusiastic amateurs’. But there’s the problem – rural Australia suffers from the tyranny of distance and it can take many hours for expert retrieval help to arrive. Add to that the fact that the more rural you go, the more likely it is that the ambulance will be staffed not by career paramedics, but by volunteers – local farmers, office workers, business people who have undergone training to a Cert IV level in ambulance.

Yet in the background there is the realisation that critical illness does NOT respect geography. Rural trauma is not uncommon and tends to be severe – the high-speed, unrestrained rollover – the arm degloved by a PTO shaft – the fall in isolated bushland etc.

Kerang Disaster & Rural Doctors

A recent illustration of this was the Kerang train crash – local doctors, many with advanced airway and resus skills – were disappointed at not being allowed on the scene. The Coroner seems to have fudged this issue, calling for ‘emergency management coordinators to be aware of the importance of including representatives of all the support services involved in the emergency response in the emergency Management Team‘

You can read more of the Coroner’s report into Kerang here and download the findings here

The RDAA put out a press release at the time and it was reported that there was some angst about not utilising local doctors at the scene.

Enthusiastic Amateurs vs Tyranny of Distance

I understand that ambulance & retrieval services do not want enthusiastic amateurs on scene – and agree with this sentiment entirely. There is, frankly, little point in the local GP arriving at a rollover with no PPE, no kit and no understanding of the prehospital environment – let alone the fact that rural docs are a heteroegeneous bunch – some have advanced airway skills, some do not….and yet it is the same ambulance and retrieval services who call the rural doctor out when they cannot respond as soon as needed.

So it has always puzzled me – there appears to be NO formal system to involve rural proceduralists (“not just a GP” but doctors with skills in resus and airway management) to ‘value add’ to the scene.

The UK has BASICS (british Association of Immediate Care Schemes) – New Zealand has PRIME (Primary Response in Medical Emergencies) – and yet these are small countries with relatively shorter retrieval distances than rural Australia. Both are designed to get the RIGHT PERSON to the RIGHT PLACE at the RIGHT TIME ie : utilise a cadre of trained clinical staff (doctors, nurses) to respond to an incident to SUPPORT ambulance staff prior to transport &/or retrieval.

SA leads the way with Rural Emergency Responder Network

We had nothing like this in Australia – and seemingly no push for this sort of network from either RACGP (as expected), ACRRM (bit disappointing) or RDAA (surprising!).

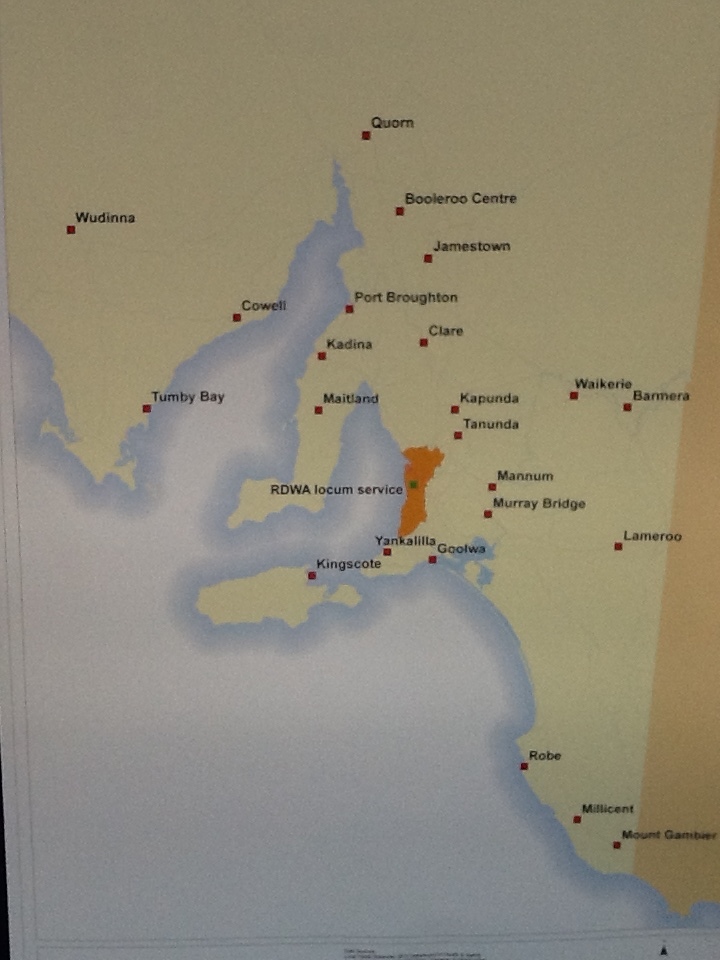

But in recent years the SA Health department has created the Rural Emergency Responder Network – and in Nov 2013 RERN won a prize in the SA Health awards.

You can read more about RERN & prehospital care by clicking HERE or watch the short video below.

One of the things that sets RERN apart from other agencies (such as BASICS) is that doctors are paid for their time (at rates better than usual call out fees) AND the system allows “opt out” – if unavailable or committed elsewhere. Doctors are also kitted with PPE and equipment.

Call outs are infrequent. There is really NO place for calling a RERN doctor unless he or she can value-add to the scene – such as delivering an aliquot of ketamine to facilitate extrication, performing finger thoracostomy or advanced airway management including drug-assisted prehospital RSI. This is tiger territory for the ‘occasional intubator’ or untrained/unequipped rural doctor.

The challenge will be to extend this paradigm across rural Australia – because sure as hell, rural emergencies will continue to happen and local doctors will be called – better that such responses are coordinated and audited, and delivered by trained & equipped personnel.

Of course one can intuitively suggest that such a cadre of rural proceduralists may be mobilised in other disaster – bushfire, earthquake etc. and offer an extra resource of emergency care and LOCAL knowledge in Australian disaster management.

I guess it will be up to rural doctors to drive this – because rural emergencies will continue to happen and we have to decide either to opt out and leave it to the experts (folly in a country the size of Australia) or be serious about how rural docs can deliver best care.

Because if we are not serious about delivering emergency care, no-one will take us seriously.